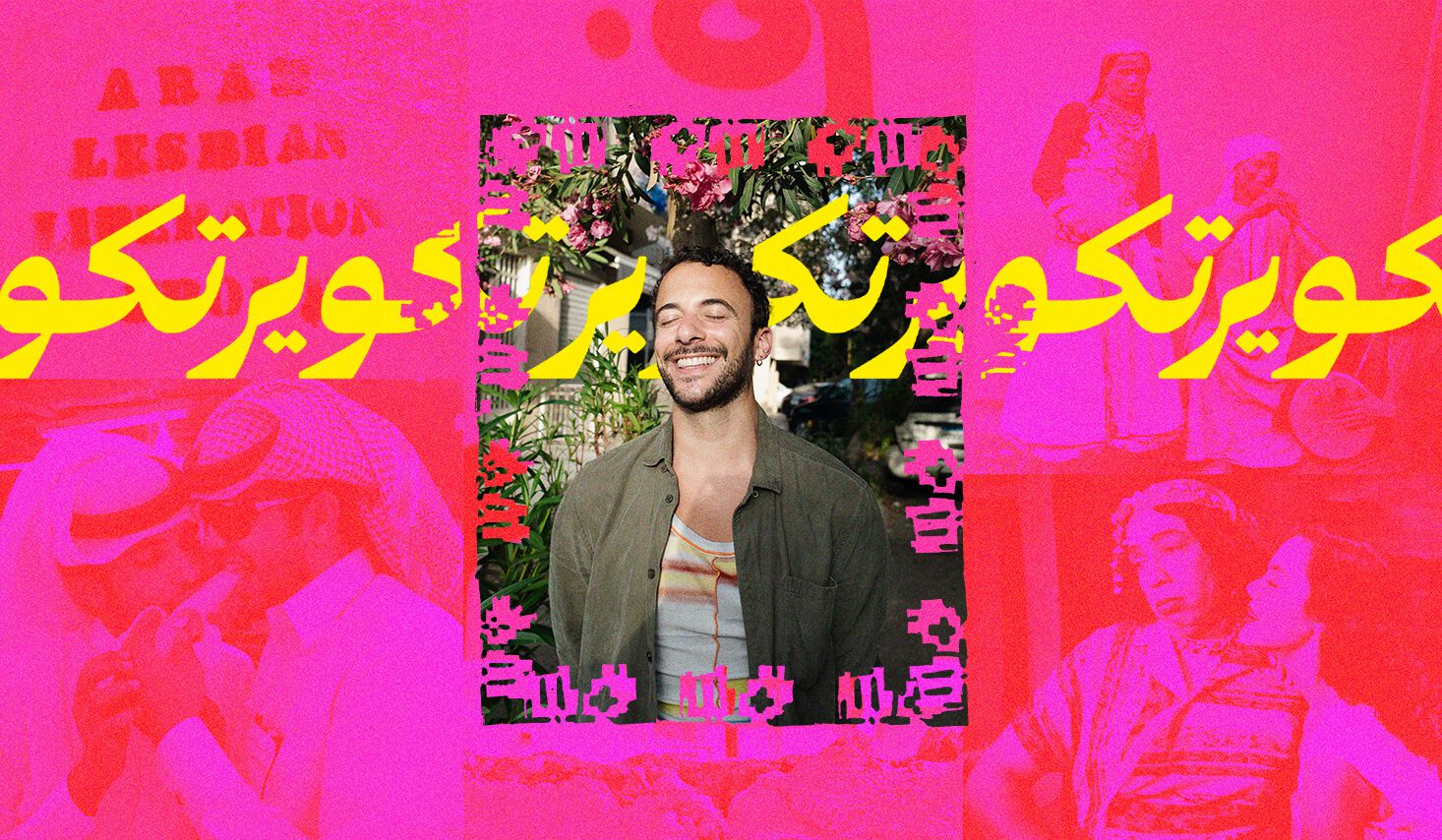

Marwan Kaabour’s long-running fascination with language has never just been about linguistics. Rather, it’s been a pursuit of self-knowledge: a way to explore the intersections of his queer and Arab identities. Case-in-point? Kaabour is the founder of Takweer, an Instagram archive dedicated to Arabic-speaking, LGBTQIA+ history and pop culture. And the idea for the page’s creation first came, naturally enough for him, by way of words.

While the page launched in late 2019, the idea was born two years earlier, when Kaabour was struck by the sonic parallels between the Arabic word “takwir” (“to make a world”) and the English word “queer”. What would happen if these two words, and their very different meanings, came together? To find out, he melded them into the portmanteau “takweer”: an expression to which he assigned the signification “to make queer”.

This act of wordplay helped Kaabour to view the Arabic language through a queer lens – a route which he was also able to pursue via Takweer. As well as collating clips of LGBTQIA+ icons from the Arabic-speaking world, the account encourages its followers to engage with culture in the region in a new way – highlighting works that might not be explicitly queer, but which carry themselves with an irrepressible wink of camp.

Creating a digital queer community

Takweer quickly gained traction thanks to its very first post: a clip of trailblazing Egyptian diva Sherihan. The page quickly developed a robust online community, in no small part due to what Kaabour refers to as “the lack of other platforms for and by the [Arab, queer] community”.

Responding to a gulf in online representation, the page built its reputation as a treasure trove of queer, sex positive and often highly memeable history: from gay-coded characters on Lebanese sitcoms to sexually provocative Syrian singers, Egypt’s first ever trans film, and androgynous mythical creatures in Islamic culture.

Rooted in the queer, Arab perspective, Takweer allows this same community to reestablish overlooked narratives from its past. “We need to carve out and document our part of history and take ownership over it,” Kaabour says. “Put it into our own words, and not have it endlessly relegated to footnotes or stuck between the parentheses of a misguided heteronormative writer. It’s important to document these instances to avoid them being lost or forgotten.”

Even in its infancy, Takweer had managed to engage a diverse cultural and ethnic audience from across the SWANA region – and for good reason. But Kaabour wanted to push the account, and what it could do, even further. He didn’t want Takweer to just be known for its attachment to the past; he wanted to pay homage to the activism of today, too.

Beginning with a post that celebrated trans Arab women for Trans Day of Visibility, Kaabour has grown the page into a vital online resource for the queer Arab community. Whether posting about the tragic passing of queer Egyptian activist Sarah Hegazi and Saudi trans woman Eden Knight, Takweer has surpassed its beginnings as a viral meme page to a “communal space” for users to engage in dialogue, find moments of joy and come together. For Kaabour, the value of this can’t be underestimated. “It’s also crucial in providing a sense of belonging and safety for the community: to tell them that you’re not alone, our folk have been here from day one and continue to do so.”

But if there’s one thing to take from a project like Takweer, it’s that queer Arabs have always existed: no matter what Arab authorities, media, and families who claim that queerness is a ‘Western import’ might think. Hopefully, by bringing together so many queer, Arabic stories from across the decades, the page can help remind people of a time when there was more openness to difference [in the SWANA region].

When it comes to his own community, the designer hopes to realign the narrative and allow queer Arabs to see the other side of history. “It’s to allow people to imagine a world where we can live together, without the animosity or fear connected with difference,” he explains. “It’s also to once and for all put to bed the tired saying of something [queer] going against ‘our values and traditions’ when it seemed like our grandparents and ancestors believed otherwise.”

View this post on Instagram

This Arab is queer: Takweer’s next steps

Key to Kaabour’s mission? Showing that queer, Arab youth don’t need to solely rely on westernised forms of LGBTQIA+ representation – there’s plenty in the Arabic-speaking world, at least when you know where and how to look. “I recall growing up with plenty of local references, icons, lexicon that seemed to be getting side-lined in favour of a Drag Race-dominated discourse,” Kaabour says. “I wanted to address that imbalance.”

Of course, a digital platform can only communicate so much, which is why the intentions behind Takweer are now set to manifest into another influential form – a book. Due for release in June next year, The Queer Arab Glossary is a study of how queerness is expressed in spoken dialects across the Arabic-speaking region.

According to Kaabour, queer Arab communities did what any other group would do when it comes to forming an identity: play with language. And because spoken Arabic is rich in diverse dialectic variations, each queer community across the region has its own lexigraphy and set of neologisms – even with the influence of English.

“Expectedly, a lot of slang used by young queers is informed by western slang,” Kaabour explains. “Due to the proliferation of the internet, we see that a lot of English words have entered the Arabic dialects, such as ‘boya’, an Arabisation and feminisation of the word ‘boy’, meaning a boyish girl, which is used across the Gulf region, or botmah an Arabisation of ‘bottom’ which is used in Jordan.”

Divided into eight dialects of spoken Arabic, The Queer Arab Glossary features eight essays by queer Arab writers, activists, artists, and academics to reflect on the glossary’s findings and themes of language and queerness.

Language beyond borders

While Arabic is lingua franca across West Asia and North Africa – and has the potential to unite the varied queer communities within these areas – The Queer Arab Glossary doesn’t shy away from the multifaceted history of the MENA region and how this is reflected in language.

Delving into how slang and colloquialisms reflect colonial histories as well as the languages of minority non-Arab communities, The Queer Arab Glossary highlights Ottoman Turkish words in the Levant, French words in North Africa and Kurdish words in Iraq.

Rather than being divided into nation-states, the book is grouped together by Arabic dialects like Levantine, Gulf, Egyptian, and Maghrebi. “Nation states are the result of political movements like revolutions, colonisations, and war,” Kaabour explains. “Language, like queerness, is a fluid notion that grows irrespective of political borders.”

Kaabour views The Queer Arab Glossary as the first fully realised project to come out of Takweer, and is building plans to re-envision how audiences can understand the Arabic-speaking region’s own version of queerness. “With the book specifically, I hope that we can take back ownership of our queer lingo, reappropriate derogatory words, and start using it more widely in the face of western words that have for too long been the norm within our communities,” he reflects.

However, for now, the graphic designer takes pride in how Takweer has grown into its own after four years. “I never thought that the ideas I had in my head would be welcomed and embraced in the way they have been,” he says. “It only goes to show the thirst for a space that the queer Arab community can call their own.”

The Queer Arab Glossary by Marwan Kaabour will be published June 2024 via Saqi Books.